Global anti-China sentiment is currently at its highest point since June 1989 when government-deployed troops opened fire on peaceful protestors in the nation’s capital. The reasons for this hardly need to be stated — in the past couple of years we’ve seen the US and China become embroiled in a trade war; we’ve seen violent crackdowns on pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong; we’ve seen China’s leaders pursue an increasingly aggressive foreign policy; and now the entire world has been brought to a standstill by a pandemic originating in Wuhan. The Chinese government certainly has a lot to answer for but there is so much more to the country than what we read in the headlines of the international press. It is, after all, the world’s oldest civilisation and is home to nearly 20 percent of the global population. I could have written a piece debunking some of the common myths about this deeply complex country but I decided instead to post the long-overdue conclusion to a two-part story about the China that I personally know and love in spite of its shortcomings. In doing so, I hope to demystify China for readers who have little or no knowledge of what life is like there and to offer a counter-narrative to all the fear-mongering that dominates the headlines. Because the things we have in common with one another are far greater than the things that divide us. If you’d like to read Part 1 of this piece, you can do so here.

“There are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there. The other is to walk round the whole world till we come back to the same place.”

G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man

“I realize now that the road is bare

The War on Drugs, In Reverse

And I hear it all through the grand parade

And I don’t mind you disappearing

‘Cause I know you can be found.”

I made my way down to breakfast in the early morning, groggy after a restless night. Mr Kong was already in the hotel cafeteria with the others, bright as a button, oblivious to the torment he’d put me through during the night, and enthused for all the adventures the new day would bring.

Breakfast was simple — baozi (steamed buns with a pork filling) and hot soy milk — but it would keep us going until lunch. Mr Kong took a rather ascetic approach to mealtimes, anyway. “Food is just fuel,” was his refrain whenever we ate together in the office cafeteria. He would eat to stave off hunger or occasionally to sample different regional cuisines, but rarely to savour the taste of his food. “We are just eating machines,” he used to say. Nonetheless, even he had grown bored of the meals at the office and the two of us had begun to frequent other eateries in the vicinity — a cheap, hole-in-the-wall dumpling place; a noodle bar that served large bowls of la mian, or “pulled noodles”; a Sichuan-style restaurant that made surprisingly good stir-fried pig intestines; and a fast-food joint that served excellent hong shao rou, a braised pork belly dish that was apparently favoured by Mao Zedong.

Sometime after breakfast, a senior military officer, a friend of Mr Zheng’s, showed up at our hotel in uniform. He had offered to take us to Pingyao and use his influence to get us into the historic parts of the city free of charge. He greeted all of us with great enthusiasm, as though we were old friends, despite the fact that we were all, with the exception of Mr Zheng, complete strangers to him.

Following a hearty exchange of salutations and small-talk we all set out from the hotel, the officer leading the way in his car. As we drove through town, I got a good look at the streets. Taiyuan seemed to be a fairly typical provincial Chinese city — there were the usual bland-looking department stores, high-rise buildings and garish advertising hoardings, and the wide roads buzzed with family cars, red-and-white taxis, microvans (nicknamed mian bao che, or “bread loaf vehicles”) and a few boxy tuk tuks. Apart from the traffic, there was little activity. But here and there the sidewalks were strewn with shreds of red paper left over from exploded firecrackers, the remnants of New Year celebrations.

The journey from Taiyuan to Pingyao was largely uneventful. We stopped along the way at a restaurant which was, like our hotel, operated by the People’s Liberation Army. Our uniformed host treated us to an extravagant lunch, ordering all the choicest delicacies on the menu. But his generosity did not end there. Once we had reached Pingyao he presented us with wrapped gifts — bottles of red wine and, oddly enough, baroque dressing table mirrors that wouldn’t have looked out of place in Marie Antoinette’s boudoir.

To a Western mindset it might seem strange that this man would go to such great lengths to show hospitality to people he’d met for the first time and would likely never see again. That’s because Western culture is fundamentally individualistic whereas Chinese and other Eastern cultures view the individual in relation to the wider community. If an individual is to thrive in China, they must build up a strong network of relationships based on reciprocity and trust. The Chinese have a word for this which is repeated often in business circles — guanxi. By making sure that Mr Zheng and his friends and family felt welcome on his turf, the officer was enhancing his guanxi and, by extension, his social standing.

Guanxi opens all kinds of doors in China — indeed, an individual won’t get far without it in a country of one and a half billion people, regardless of professional qualifications. There were certainly occasions where I had made use of it myself. For instance, a well-connected businessman named Mr Zhu had hooked me up with a “Foreign Expert Visa”, despite the fact that I was one year shy of the minimum eligible age of 25. In return, I had proofread copy for some in-flight magazines his company produced and attended several plays about the life of Che Guevara put on by an acting school he’d invested in. It was a pretty good trade-off for me since I probably wouldn’t have been able to work for a local media company without that visa. That is the magic of guanxi.

On arrival in Pingyao, we parked just outside the city’s walls — soaring crenellated ramparts which stood starkly against the blue, slightly hazy springtime sky — and headed for the south gate. Pingyao is one of the few Chinese cities that still has all its defensive walls intact. Its fortifications have existed in their current form since the Ming dynasty, the same era in which most of the Great Wall was built, and they look just as formidable today as they would have done all those centuries ago.

The walk to the south gate, or Ying Xun Gate, took us past a series of gaudy Chinese New Year displays, their tackiness clashing with the grandeur of the ancient masonry looming above us. There was a queue of visitors at the gate but our uniformed friend took as right to the front of it and had the ticket inspectors let us in for free, as he had promised. Then, having made sure we were all well catered for, he bid us farewell and set off for his academy.

I said that guanxi has the power to open doors in China. In this case, it had opened up an entire city. We entered old Pingyao through an imposing barbican which opened onto a scene that hadn’t changed much since the city’s 19th-Century heyday. Before us was a flagstone street which cut straight through the city between imperial-era shops with sloping tiled roofs. Pedestrians and cyclists thronged the street, red lanterns suspended above them between the rooftops.

There was much to explore, but first we would get up onto the ramparts so we could view the entire city from above.

About a month before quitting my job and leaving Beijing, I ventured downtown to say farewell to some friends of mine — Alex, a Canadian-American elementary school teacher, and Sebastian, a born-and-raised Beijinger who was studying French at college. We had dinner at a slightly upmarket Sichuanese restaurant and then headed to Sanlitun, a commercial district popular with the expat crowd, for drinks. Sebastian recommended a sleazy-looking bar called Pure Girl, one of a number of dives in the area that was later shut down by the authorities due to its alleged involvement in drug trafficking. But Alex and I vetoed Sebastian’s suggestion and we instead ended up round a bay window table in a cosy pub sharing stories over pints of beer. Outside, snow drifted down and blanketed an eerily quiet lamp-lit street. It was mid-March, the beginning of the Year of the Dragon, and this was the snowiest day we’d seen all winter.

Sebastian had brought along a girl he had met that afternoon in a French library, a college student who introduced herself as Claire. Claire said she’d never set foot in a pub or bar before. And her inexperience soon became apparent — about half a beer down she began pouring her heart out to us. Not too long ago she had emerged from a toxic relationship with a French guy who had turned out to be an incorrigible womaniser. Since then, she had dated other philandering Frenchmen. She couldn’t resist “bad boys”, she said, but deep down she wanted a man she could build a stable future with. Eyes welling up with tears, she despaired that she was getting old (she was only 26) and her parents were constantly nagging her about getting married. Throughout Claire’s tearful soliloquy, Sebastian fawned over her. He too had a complicated love life — he had pursued a woman roughly twice his age, going so far as to convert to the Baha’i Faith for her, but things had ultimately not worked out between them.

Snow was rapidly building up on the road outside and a group of Caucasian girls dressed for a nightclub were dancing in it. “It’s ok for guys like you,” Claire said, indicating Alex and me. She called us “floaters” and said she wished she was free like us to roam the world; free from the rigid expectations of family and society.

Several times while we were in the pub Claire’s parents called her up to check on her and ask when she was coming home. But Claire was in a rebellious mood and stayed out past her 11 O’clock curfew. We called it a night around 1am and headed for a nearby taxi rank, heads stooped in the falling snow. Once we had said our farewells, I hopped into my cab. Alex gave a final wave before walking off into the night with Sebastian and Claire. “I hope you find what you’re looking for!” he said.

The journey home took me down Chang’an Avenue, a major road that cuts right through the political heart of Beijing. The city looked ethereal in the snow and streetlights, its pavements deserted. Tiananmen Square, flanked on two sides by the starkly illuminated porticos of the Great Hall of the People and the National Museum of China, was ghostly quiet. North of the square, the Gate of Heavenly Peace, or Tiananmen, loomed in a nimbus of electric light, the sanguine face of Chairman Mao hanging from it, keeping vigil over the entrance to the Forbidden City.

My driver was in a good mood, perhaps because he was charging a high fare on account of the snow and the late hour. He offered me a Golden Bridge cigarette and chatted away in heavily accented Mandarin interspersed with broken English. He liked English people, he said, but not Americans (an interesting viewpoint considering the brutal history of Sino-British relations, but not an uncommon one). He took out his phone to show me pictures of his dream car, a Bentley. “Yingguo zhizao (made in England),” he said with a thumbs-up, but “tai gui le! (too expensive!)”. He said he practised kung fu, or gongfu as it’s known in China, but I don’t know whether he really did or he was just playing up to Western stereotypes about Chinese people. He demonstrated a few moves but I was too focused on his no-hands driving to judge his skill as a martial artist. Whenever we stopped at a red light, he would hop out of the car to clear the windshield of snow, which was coming down so heavily it had crippled one of the automatic wipers.

As I watched the sleeping city glide past my window and listened to the driver ramble on, I felt a sense of profound contentedness. I had made Beijing my home for nearly three years. Although there was still much that I didn’t understand about the city, I felt I knew it well enough to call myself a Beijinger. My grasp of Mandarin was nowhere near what it could’ve been if I’d been more intentional about learning it, but I’d come a long way, as evidenced by the fact that I could not only give my cabbie directions, I could also just about keep up with his scattergun commentary on luxury cars and martial arts. Having wrestled for years with a sense of rootlessness, I knew what a privilege it was to have had the opportunity to stay in one place long enough to experience the extremes of its beauty and its ugliness, to be thrilled and maddened by it, to see the seasons change, to witness its history unfold, to observe the nuances of its culture, to partake in its festivals, to befriend its people — in short, to get acquainted with it on a deeper level than a visitor ever could.

At the same time, I felt a slight pang of regret that I’d not made more of my time in Beijing. When I’d first moved to the city I’d seen it as a chance to start over — a chance to find my calling and my place in the world at a time of great uncertainty and doubt. I’d graduated in the year of the Global Financial Crisis and, like many of my peers, faced a future of scuppered dreams and unrealised potential. The prospect of managing a business newswire in the dynamic Chinese capital had seemed preferable to scratching out a living as a barista or shop assistant in some sleepy English market town or, worse still, queuing up at the local Job Centre week in and week out to claim unemployment benefits. I’d spent a large part of my childhood and adolescence in China during the boom years of the 1990s and early 2000s and had witnessed the country’s astonishing rise up close — I knew that if any country was to weather the coming economic winter, it’d be China.

Indeed, moving to Beijing had been good for my professional and personal growth. While the Western world seemed to be unravelling, I felt like I was riding an unstoppable wave. England’s glory days were a fading memory, but China was a world brimming with possibility. But there was an emotional cost. I struggled to keep up with the solid work ethic of my Chinese colleagues who worked all day in the office and studied for exams at night. There’d come a point where I felt out of my depth and crippling self-doubt threatened to overwhelm me. Far from finding my place in the world, I’d succumbed to a growing sense of alienation. I’d failed to assimilate fully and that years-old feeling of rootlessness lingered.

I thought about Alex’s parting words. What was I looking for? I wasn’t entirely sure. On some primal level, I craved meaning, truth and purpose, just like anybody else. But this inner yearning was frustrated daily by confusion, boredom, depression, fear and a sense that every human endeavour was an exercise in futility. I’d come to feel that the most I could hope for was to coast through life — to experience as much of the world as possible while I had youth on my side and to make every effort to dodge commitment and responsibility.

The trick, I thought, was to go with the flow — to always opt for the path of least resistance and to travel light. I didn’t realise it at the time, but in a simplistic sense I had embraced the concept of wu wei, or “effortless action”, a key tenet of the ancient Chinese religious tradition known as Toaism, or Doaism. The harder I searched for meaning, the less likely I was to find it. So I thought.

Alex, one of only a handful of expats I’d got to know during my time in Beijing, had the kind of easygoing, carefree disposition I aspired to. Back at the pub he’d regaled us with tales of high jinks and adventure across China. He’d once got blind drunk and slept on a street in Wudaokou, Beijing’s university district. He’d flooded a hotel room in Macau, China’s gambling capital, after passing out drunk in the bath. And, most amusingly of all I thought, he’d attempted to paddle from Guilin to Yangshuo with a group of friends and ended up sleeping in a cave by the river before selling the dinghies to some local farmers and hitchhiking the rest of the way.

On paper these stories read like the shenanigans of an overgrown frat boy but to me they were reminiscent of Jack Kerouac and other beat generation writers I admired. I had picked up a pirated copy of On the Road from a street vendor in Wudaokou during one of my long, aimless walks and was instantly drawn in by the freewheeling exploits of its manic protagonists. Kerouac’s writing seemed at the time like the only rational response to the transience of human existence. “I had nothing to offer anybody, except my own confusion,” he proclaimed, and I felt like there was something heroic in those words.

But Alex was neither an overgrown frat boy nor a crazy beatnik. Far from it. As much as he knew how to get his kicks, he had a mellow personality and came across as remarkably level-headed and down-to-earth in his relationships and professional pursuits. He had found his niche in the city with seemingly little effort. His Mandarin was better than mine despite the fact that he’d spent less time in China than me and he’d recently been offered an interesting-sounding job at an expat publication. He’d even met his future wife — a demure, intelligent girl from Shandong Province.

While I was winding down my time in China, Alex was just getting started. It would be a few more years until I found a wife and settled down (in another Asian megacity, as it happens) and in the meantime all I knew was confusion. I felt like a gnat in a hurricane — powerless and disoriented, hurtling through a chaotic void. I was heading back to England for lack of a better idea but I didn’t know what I’d be doing work-wise and I had no home of my own there. I admired Alex’s ability to live in the moment, Kerouac-style, but what I really envied was his apparent self-possession. I wanted what I saw in him — the freedom to roam and the courage to settle. And deep down I knew that a freewheeling sort of life could lead only to emptiness in the long run. Kerouac’s characters were a sad bunch, really. And the author himself, for all his Benzedrine-fuelled adventures in the quest for enlightenment and “beatification”, couldn’t keep his demons at bay — he was dead of cirrhosis at 47 after years of depression and alcohol abuse.

Thankfully, alcoholism had never been an issue for me, despite the fact that a bottle of beer could be bought in Beijing for less than the price of a bottle of water. I had, however, become well acquainted with depression. I’d been wracked with it for most of my adult life up until that point. I was jaded. Things that once gave me joy no longer did. Books, films, music — everything was a drag. Even the prospect of travel was no longer exciting to me. I had seen a lot of the world by the time I’d reached my twenties and yet I felt more detached from it than ever before. I had had more than a lifetime’s worth of memorable experiences and yet I felt somehow that I wasn’t leading a full life. I had met many people on my travels and yet most of my relationships felt ephemeral. I was getting used to an insular existence and yet I felt that somehow all the things that I’d seen and felt and learnt didn’t count for anything unless I had someone to share them with.

It so happened that I had discovered the writings of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard around the same time that I was getting into the beat writers. I had picked up a well-thumbed second-hand copy of Works of Love at the Bookworm, a literary hub in Sanlitun where I would often wile away the hours on weekends, and encountered within its pages a message altogether different to Kerouac’s.

Kierkegaard wrote about the “royal law” — that is, Christ’s commandment to love one’s neighbour as one’s self. This commandment, which I’d heard so often it had been reduced to a platitude in my ears, took on fresh significance for me thanks to Kierkegaard’s book.

What struck me most was the book’s assertion that neighbourly love is the highest form of human love — it is purer than other forms such as friendship or romantic love since the others are self-serving to a degree. But Kierkegaard was not talking about some nebulous love for “humankind” — “At a distance every man recognizes his neighbour,” he said, “and yet it is impossible to see him at a distance. If you do not see him so close that you unconditionally before God see him in every man, you do not see him at all.”

Kierkegaard’s thoughts on the royal law took me off guard. They were not saccharine or wishy-washy in the way that meditations on love often are. They made me uncomfortable the way truth usually does. For I gravitated to misanthropy. I had my small circle of friends and loved ones but I regarded the human race en masse as a plague — a degenerate, bestial, irredeemably violent species that had managed to colonise every habitable corner of the globe despite a peculiar genius for self-destruction. When I looked at the human race, supposedly made in God’s image, I sometimes wondered if God himself was malevolent, or at least indifferent to the evils perpetrated by his creatures.

I had spent a lot of time in large cities and the paradox of large cities is this —all the trappings of civilization and the layers upon layers of culture seem only to accentuate the brutishness of their inhabitants. To me, this was one of the most alluring features of cities — the way they simultaneously showcased humans at their most brilliant and at their most absurd, superficial and debased. I had become increasingly content with watching the burlesque of city life from the wings instead of taking part. But if I was in danger of becoming a total prig, excessive introspection helped keep me grounded. In fact, I had eventually become so preoccupied with my own inner darkness that I hardly engaged with the world around me at all.

Strange as it may seem, I don’t recall ever meeting my immediate neighbours in Beijing. Only in the most crowded cities is it possible to be oblivious to the existence of others even when living cheek by jowl with them. I heard them through my bedroom wall, almost on a daily basis — a woman’s voice raised in anger followed by the bawling of a child. The more the woman shouted the more the child cried and the more the child cried the more the woman shouted. Perhaps it was my delicate Western sensibilities, but I couldn’t imagine any scenario in which a child’s behaviour would warrant such intense scoldings. It occurred to me once or twice to intervene and get the woman to calm down. But I could barely string a sentence together in Mandarin — what would I say? And was it any of my business what people did in the privacy of their own homes?

I preferred not to get involved in the lives of my next-door neighbours if I could help it. I cherished solitude. Perhaps that’s why the royal law, seen afresh through Kierkegaard’s eyes, seemed so radical and counter-intuitive to me. If it had simply said “live at peace with your neighbour” it would still have been hopelessly at odds with human nature but at least it would have made sense to anyone who wishes to live in a harmonious society. But it called for indiscriminate, non-preferential love, not merely peace.

As someone hailing from the individualistic West and raised under China’s reciprocation-based system of guanxi, Kierkegaard’s book was a revelation to me. On one hand, it was liberating since it spoke of a kind of love that is not dependent on feeling — a kind that goes deeper than romance or mere altruism. For if love is a command, it follows that it is possible to love one’s neighbour without first finding them naturally loveable or even likeable. On the other hand, it was damning since no one truly loves everyone they come into contact with.

Not that Kierkegaard thought that works of love are a means to salvation. “What you learn first of all in relating yourself to God is precisely that you have no merit at all,” he wrote on the last page of the book. His God was a God of clemency, not a score-keeping tyrant. And it occurred to me that if mere mortals are capable of expressing selfless love, the highest and rarest of virtues, how much more must their creator be capable of it. Nevertheless, I felt convicted by Kierkegaard’s observation that one can only truly love one’s neighbours if one knows God and, conversely, those that don’t love their neighbours don’t know God.

Perhaps Kierkegaard’s book resonated so strongly with me because it underscored a truth that stood in stark opposition to my desire for independence. As much as I tried, I couldn’t get around the fact that human beings are hardwired for connection — with their creator and with one another. And it is surely impossible to forge meaningful connections without a certain amount of intentionality, commitment and even self-denial. “How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it,” the author GK Chesterton wrote, and I thought about his words often.

Indeed, in my suburban isolation, deprived of a proper community, I felt as though my world was becoming more confined and claustrophobic. How had it come to this? Claire had not been too wide of the mark when she’d called me a “floater”, though I detested the word. For I was unmoored and directionless — a piece of flotsam drifting with the ocean currents. The few meaningful connections I’d made in Beijing had taken a long time to develop and now I was moving on once again, fully aware that it was unlikely that I’d ever see these friends again.

Like many young adults in China, Claire dreamed of getting out into the world, a dream that was inconceivable to her parents’ generation. I understood how privileged I was and that there was a lot to be said for a life of travel — it had brought me into contact with numerous people, cultures and worldviews that I would never have otherwise come into contact with. But I didn’t have the heart to tell her that it was a transitory and solitary sort of life and, in that sense, an incomplete sort of life. I didn’t tell her that “home” is a criminally underrated thing.

With my time in China at an end, I knew the long search for home would continue. But I was more certain than ever before that this thing called home is not a place, it’s people. And I knew that it was worth finding even if it meant relinquishing my independence.

The view from the ramparts of Pingyao was spectacular. The sloping roofs of the city spread out before us like the waves of a grey sea, parted down the middle by the bustling high street.

The high street was overlooked at either end by three-tiered towers with tiled eaves. The tower at the southern end, the tallest structure in the old city, loomed over us from its position atop the barbican, its eaves decorated with carved dragons and other mythical beasts. The tower at the northern end straddled the street, a constant flow of pedestrians passing through its built-in archway. Roughly a kilometre from where we stood, the north tower looked wraithlike in the haze that permanently hovers over cities in China’s coal belt.

The residential areas were mostly made up of traditional courtyard houses known as siheyuan. The larger ones stood as witnesses to the prosperity that once existed in the city. However, most of them were in a state of disrepair, with paint and plaster peeling off their walls and dusty furniture strewn around their courtyards. If it weren’t for the fresh new year decorations and the odd wisp of smoke issuing from a stovepipe, I would have thought the ancient dwellings were unoccupied. Perhaps the residents had permanently withdrawn from their courtyards to avoid the prying eyes and cameras of the hundreds of tourists, like us, who stroll along the city walls above their heads each day.

The layout of the walls on which we walked was said to resemble the outline of a tortoise, the south gate representing the head, the north gate the tail and the four gates of the east and west walls the feet. Studded with watchtowers, the walls formed an almost perfect square, straight on three sides and serpentine on the south side.

Once we had got all the photos we wanted (Mr Kong snapped away on his DSLR like a trigger-happy paparazzo) we descended from the wall and headed for the shopping street. We passed vendors selling intricate red paper cuttings, candy floss and helium balloons in the shape of cartoon characters. Amid the melee of shoppers and sightseers, a donkey and carriage decked out in festive colours stood motionless. The driver’s skullcap and Turkic features indicated that he was a member of the Uyghur community, a minority ethnic group native to Northwest China.

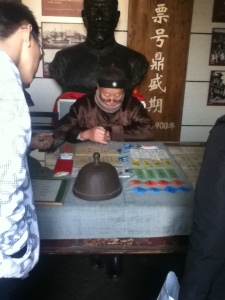

To walk through Old Pingyao is to take a trip into China’s past. The city seems to have been almost completely sidelined by the wave of rapid urban development that has swept across the country in the past few decades — ironic, perhaps, considering it is credited with giving rise to modern China’s banking industry. Back in the early 19th Century, when Pingyao was a booming trade hub, a dye company based in the city implemented a system whereby money could be transferred using paper “drafts”, cashable at any of its branches, thus removing the necessity of transporting large amounts of silver. The idea caught on to such an extent that the owner of the company withdrew altogether from the dye business and established Rishengchang Piaohao, China’s first bank. Several other banks soon emerged in the city, complete with opium dens for VIP guests, but none were as successful as Rishengchang. At the height of its success, the former dye company supposedly controlled nearly half of the Chinese economy.

But Pingyao lost its economic clout with the fall of the Qing dynasty in the early 20th Century and faded into obscurity as China became engulfed by war and revolution. Rishengchang began operating at a loss and was finally forced to close when the Great Depression of the 1930s hit. Poverty stricken, Pingyao entered a period of stasis which lasted until UNESCO recognised its historical and cultural value and granted it World Heritage status in 1997. The UNESCO listing caused the city to be reborn as a tourist destination, although it remained off the radar of most international tourists until recent years. Visitors now flock to the walled city from far and wide to marvel at the imposing Ming and Qing architecture which stands as a potent reminder of a long-lost golden age.

I saw hardly any foreign tourists as I walked around Pingyao, but I could tell by the numerous English signs for backpacker hostels that they must visit in significant numbers in the warmer months. Most of the people milling around on the high street that day were, like us, Spring Festival holidaymakers from other parts of China. They moseyed along in groups, sampling street food and browsing through shops selling all manner of curiosities — animal skins, porcelain dishes, swords, Mao figurines, calligraphy brushes, tiger paws (a grisly ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine), jade coins, prayer beads, traditional woodwind instruments made from gourds and sticks of bamboo, collectible walnut shells (prized as a status symbol by wealthy Chinese) and so on. Perhaps a similar scene would have greeted visitors to Pingyao in the days when the city thrived on trade flowing between southern China and neighbouring countries to the north.

While Mrs Chang and Ling Ling went off to buy some earrings, the rest of us perused the wares on display. Among the memorabilia shops selling old communist propaganda posters and portraits of the iconic singer and actress Zhou Xuan, there was one picture that caught Mr Kong’s eye — a headshot of a moon-faced gentleman sporting a Mao suit and closely cropped hair. This, he informed me, was Hua Guofeng, a politician who served as China’s premier in the 1970s. Hua was born just down the road from Pingyao in Jiaocheng County but it was in Hunan, Mr Kong’s home province, that his political career first got off the ground. As we walked around, we noticed that portraits of Hua were almost as ubiquitous as those of Mao, and though Mr Kong generally cared little for communist politicians it amused him greatly to find a Hunan connection so far from home.

Mr Kong’s fondness for his hometown was matched only by his curiosity about people from other places. He was keen to meet the locals of Pingyao and quickly struck up conversation with a man preparing dragon’s beard candy, a traditional Chinese sweet made of gossamer-thin sugar-strands, a little like candy floss. I watched, transfixed, as the man stretched a toffee-like substance over a metal hook, working it into a thick golden ring. And later, when wandering the backstreets, Mr Kong chatted to an old lady who was cooking in a poky kitchenette that opened onto the street. These interactions pleased him immensely.

For all his eccentricities, my boss had some truly admirable qualities, and his ability to connect with people of different backgrounds and social strata was one of the qualities that impressed me most. He got along well with foreigners and had an affinity with much of Western culture, so much so that he’d been vilified as a “foreigner’s dog” on several occasions. He had befriended the often-overlooked car-park attendants in his neighbourhood and sometimes sat with them in their cabin over food and baijiu. His circle of closest friends included an artist, a violin instructor and several entrepreneurs. Despite profound ideological differences, he wasn’t averse to engaging with cops and Communist Party apparatchiks. And he was not afraid to be seen fraternising with the solitary protesters chalking their grievances on the sidewalks of Beijing. These people — mostly folk from provincial China who were seeking redress at the Supreme People’s Court for local government injustices — were technically breaking the law by mounting unauthorised protests, but Mr Kong sympathised with their plight. To him, meeting someone new was not merely an opportunity to enhance his guanxi, it was an opportunity to learn more about the world around him.

in Rishengcheng Piaohao.

Once we were reunited with Mrs Chang and Ling Ling, who had been successful in their quest, we decided to check out the city’s main attractions. One of these was the property that once housed the aforementioned Rishengchang bank, a large compound with tiled roofs, wood panelling and lattice windows. There were also several ancient temples dedicated to Daoism and Confucianism scattered throughout the eastern half of the city. But there was only so much culture I could absorb in one day and when I think of these places now I can only picture old courtyards thronging with large, noisy crowds.

One of the most memorable sights was the prison attached to the old government office complex. Mr Kong horsed around and posed for pictures in one of the cells, pulling a woebegone expression as he clung to the bars. The cells were all pretty Spartan, but the ones for high-status prisoners were fitted with a few creature comforts, including a kang, a traditional coal-heated bed of the kind found in homes throughout northern China.

The prison museum was full of macabre-looking objects, the most disturbing of which was what appeared to be a wooden rocking horse with metal spikes embedded in its back. The objects were helpfully categorised with bilingual signs reading “torture instruments of custody”, “torture instruments of execution” and “torture instruments of interrogation”. Mr Kong immediately took a morbid interest in these items. If he’d not become a businessman, he’d have become an undertaker or gravedigger, he told me once. “Death is real life,” he had said, somewhat paradoxically.

Once we had taken in the sights, we headed back towards the south gate of the city. Having built up an appetite with all the walking, Mr Kong and I approached a vendor selling what at first glance appeared to be a local spin on one of my favourite Chinese street foods, roujiamo, a type of sandwich consisting of flatbread and pork belly. But, on closer inspection, this man’s product looked more like a fajita and the filling, it turned out, was donkey meat, not pork. Mr Kong took one bite and immediately registered his disgust with a cartoonish grimace. “I think he put rat flesh in this,” he said, turning the thing over in his hand and eyeing it with suspicion.

“I thought food was just fuel,” I said. But Mr Kong wasn’t listening. He had spat the stuff out and flung the remainder of his wrap in a nearby bin and was now telling the vendor in no uncertain terms what he thought of his product. “Ten yuan for that garbage!” he fumed. Mr Kong rarely minced his words.

When we had all regrouped (the others had scattered for some last-minute shopping) we left the walled city and headed for the car park. In the square in front of the south gate a Beijing opera performance was underway and a sizeable crowd of people, mostly senior citizens, had gathered to watch it, some sitting on bicycles, the rest standing. We hovered on the edge of the crowd for a few moments, watching as costumed performers gesticulated and somersaulted while strident percussion and plaintive strings rang out through the square.

With that we left Pingyao and got back on the road. But there was one last thing to see before returning to Taiyuan — roughly midway between the two cities there was a stately 18th-century courtyard house that was once the home of Qiao Zhiyong, a well-known financier of the Qing dynasty.

At the entrance to the Qiao residence, Mr Zheng dropped the name of his local military friend and the ticket collectors swiftly arranged a free guided tour for us. The house was very grand — one of the finest remaining examples of a siheyuan — and its 25 courtyards were steeped in history. It was also the setting of the classic film Raise the Red Lantern, which tells the story of the rivalry between the concubines of a wealthy man in the early 20th Century. But I had no energy for the hordes of camera-toting tourists jockeying for the best picture angles and was somewhat relieved when our tour came to a conclusion.

The light was beginning to fade when we emerged from the Qiao property. The route back to the car park had been taken over by a flea market. We walked between stalls selling broadswords, decorated bottle gourds and an assortment of knick-knacks and paused at a table on which two shifty looking characters were displaying sniper scopes, handguns , slingshots and binoculars. The guns were almost certainly replicas since civilians are not allowed to own firearms in China, but the two guys manning the table looked as though they’d be able to hook you up with the real deal upon receipt of a secret password or something. Mr Kong and Mr Zheng examined the items on display and engaged in banter with the sellers. Mr Kong was passionately opposed to gun control (a bone of contention between the two of us) and nothing got him fired up quite like the thought of an armed citizenry rising up in insurrection against the government. Mr Zheng presumably did not share his friend’s views — the government was, after all, his paymaster.

Evening had well and truly set in by the time we got back to Taiyuan. Despite the long, eventful day we’d all had, Mr Kong was raring to get back on the road and drive the nearly 500 kilometres back to Beijing. Thankfully, his wife talked him into staying one more night in Taiyuan.

But we were not quite ready to call it a day and decided to take an amble through the streets around our hotel. We stopped when we came across a couple of Uyghurs selling chuan’r, a type of kebab, and Mr Kong struck up conversation with them while they fanned the coals and turned the skewers.

Like many Uyghurs, these men had travelled east from Xinjiang, a so-called “autonomous region” in the mountainous north-western borderlands of the country, in search of better prospects. But they had not exactly received a warm welcome from the Han Chinese who make up the vast majority of East China’s population. They had instead come up against deeply ingrained prejudice, an experience all too familiar to the Uyghur diaspora. The Han majority has for a long time treated the Uyghurs as second-class citizens, with many writing them off as swindlers, thieves or worse. But the demonisation of this predominantly Muslim community intensified in the wake of the global War on Terror — and a string of terror attacks by Uyghur separatists throughout China, including a vehicular suicide attack in Tiananmen Square while I was in Beijing, only served to reinforce the community’s pariah status.

Under the pretext of combating religious extremism, the government embarked on a sinister campaign to “re-educate” and assimilate the Uyghur population. Xinjiang is now a full-blown police state where the population is subjected to heavy surveillance and individuals are routinely arrested and “disappeared” without due process. Human rights groups estimate that more than one million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities are currently locked up in “re-education camps” throughout the region.

Like any totalitarian regime worth its salt, China’s communist government has become adept at exploiting the fears of the masses to extend and strengthen its control over the whole population. But in my more optimistic moments I take heart in the fact that there are, within the masses, people like Mr Kong — firebrands demanding political change; idealists questioning the status quo; nonconformists rejecting the narrative of fear and taking a stand for a more open and fair society. Mr Kong had his prejudices, as we all do, and a host of questionable ideas to boot. But nonetheless he had an insatiable curiosity about the world — its peoples, cultures, belief systems — and that, after all, may be all that is needed to puncture the darkness. For if there’s one thing that keeps tyrants awake at night it’s the thought of people getting out of their little worlds, overcoming the things that divide them and engaging in the revolutionary act of talking to one another.

Mr Kong purchased a couple dozen sticks of chuan’r and then posed for pictures with the two sellers, smiling broadly as though he’d been reunited with long-lost brothers. And then we went on our way, enjoying our lamb skewers and chatting about the day’s highlights while the sound of firecrackers reverberated through the streets.

We ended our walk with a hearty dinner at a seafood hotpot restaurant and then returned to the hotel. Back in our room, Mr Kong stood shirtless in front of the TV, patting his belly and flipping through the channels until he settled on a film about the Second Sino-Japanese War, or the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression as it’s known in China. He was partial to war films, even those that had a strong pro-communist subtext, as this one evidently had. But pretty soon the rat-a-tat of machine-gun fire had been replaced by the all-encompassing sound of my boss’s inhuman snoring — a sound so immense it made me pine for my Beijing apartment with its comparatively gentle soundtrack of car horns, jackhammers and shouting next-door neighbours.

There is, after all, no place like home.

https://j.map.baidu.com/31/m3x

If you would like to be notified of future posts, click the “follow” button on the right-hand side of this page (bottom of the page if you’re reading on a mobile device). Even if you’re not a WordPress user you can subscribe by entering your email address below.

You can also get updates by following me on Twitter (@pushkindisco).

And you can view photos from my travels on my Instagram page (@theborderlandsblog).

If you’d like to know more about this blog, check out the About page.

Another wonderful inside glimpse of China, Sam! And profound reflections on some of life’s questions.

Loved: ‘…hope to demystify China for readers … and to offer a counter-narrative to all the fear-mongering that dominates the headlines. Because the things we have in common with one another are far greater than the things that divide us.’ Especially that last bit.

Enchanted by your rounded portrayal of characters, the unpacking of guanxi, sharing about MK/TCK alienation, rootlessness and depression, Kierkegaard’s royal law of indiscriminate, non-preferential love of our neighbour as Jesus teaches us, ‘human beings are hardwired for connection — with their creator and with one another’ (perhaps this is being rediscovered now in the Covid-19 crisis), ‘this thing called home is not a place, it’s people’, the disgusting donkey-meat roujiamo – and your reaction to your boss’s snoring.

Thank you for another great read! The guy has boundless talent!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Clive! Glad you liked it. I always like to know which specific bits resonate with people. I agree with your point about people rediscovering the importance of connection during the Covid-19 crisis. The theme was on my mind when I wrote Part 1 (before the crisis) and it certainly seems more relevant now than before.

LikeLike

Sam! I have already given you my views on this piece. You have a unique way to describe a place, its people and your adaptation to it. This piece kept me engaged to a point where I felt I could relate to it being an Indian. Always proud of your talent! Love you ♥️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you liked it 🙂 Can’t wait for our next trip (whenever that is)!

LikeLiked by 1 person